When working on scientific and technical presentations, I am often amazed by the wonders of the science being presented and, at the same time, shocked by the speaker’s lack of awe or appreciation for the mystery and power of his own work.

It seems to me that many scientific and technical speakers take their own work for granted, as if expressing appreciation for the mysteries they’re exploring would be unprofessional.

I find this tendency to be damaging to the scientific and technical presenter’s ability to create excitement and comprehension in their audiences, especially when they’re speaking to lay audiences, where it is crucial to set up the context and dramatize the strangeness and wonder of the work.

Furthermore, when the scientific or technical speaker is trying to raise money or sell an asset or idea, his ability to generate enthusiasm and curiosity helps predispose an audience to take a second look.

What can be done for scientific and technical presenters who are tasked with getting lay audiences to understand and appreciate the dramatic power of their work?

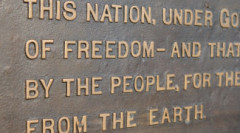

Strangely enough, the Gettysburg Address has something to teach them.

The Back Story

President Lincoln began his famous speech with the back story—the big picture. “Four score and seven…” He reached back 87 years (a score is a quantity of 20) and summarized American history in one sentence.

Scientific and technical presenters can do this too. They can summarize the work done in their particular field up until the present, implying that the project under discussion builds on a body of research that is important to humanity.

The Current Problem

President Lincoln then defined the intractable problem the country faced in the present moment. “Now we are engaged in a great civil war…” he said.

Scientific and technical speakers should do the same. Having summarized the work of previous experts, they should describe the problem that remains to be solved. This is important because it helps people take an interest in the topic.

The Question that Needs to be Answered

Then President Lincoln asked a question—not directly, but he implied one—which is, “What can I possibly say here to honor the men who died?”

He answers the question by saying that no words he can speak will do the job. Instead, he asks his audience to rededicate their lives to the “proposition that all men are created equal.”

Scientific and technical presenters can also use this technique: ask the question that needs to be answered, and then offer an answer.

For instance, a biotech firm developing on a new HIV compound might phrase such a question like this: “Given the long march HART (highly-active anti-retroviral therapy) has taken, and since, in that time, few agents in this class have made it to market, and those that did suffered from food issues and lipid abnormalities, what attributes has this compound demonstrated to justify our confidence in its ability to clear all regulatory hurdles and play a significant role in the treatment of HIV?”

The Answer to the Question

At this point in the talk, the scientific or technical presenter should proceed to make his or her argument for the value and importance of the product, just as President Lincoln made the case for honoring the dead by continuing to prosecute the war.

Delivery

Finally, the scientific and/or technical speaker must make the case with some enthusiasm. Getting others to appreciate the incredible journey science continues to take requires more than words. It requires the emotional expression of awe and wonder—an overt appreciation for the mystery of things.

After all, emotions are contagious. Without emotion, a speaker’s ideas are rarely catching.